set.seed(101)

library(ggdibbler)

library(ggplot2)

library(dplyr)

library(tibble)

library(patchwork)

# make prediction diamonds data

diamonds_pred <- smaller_diamonds

diamonds_pred$cut_pred <- smaller_uncertain_diamonds$cut

diamonds_pred <- diamonds_pred |>

rename("cut_true" = cut) |>

relocate(c(cut_pred, cut_true), .before = carat)

options(rmarkdown.html_vignette.check_title = FALSE)As the graphics made by ggdibbler are random variables

represented by a sample, they are random plots. This means that each

time you call a plot, it is different. This behaviour makes sense, as

every plot is just one of many possible outcomes you can have when you

represent a distribution by a sample. Technically the plots would be

identical if you set your times to be infinity, but an

infinite number of draws is just a tad too computationally expensive for

our package.

If you are used to the deterministic behaviour of ggplot, the randomness can be off-putting, although not technically incorrect. Most of these issue can be mitigated by using the seed option, but the behaviour can be surprising if you are not used to it (so we are documenting it here).

Saving plots

When you save a plot, ggplot2doesn’t technically save

the plot itself. It saves the code that makes the plot. It only actually

runs the code when ggplot_build() is called, which is only

called when you print the plot.

plot <- ggplot(uncertain_mtcars, aes(wt, mpg)) + geom_point_sample(times=5)

plot + plot

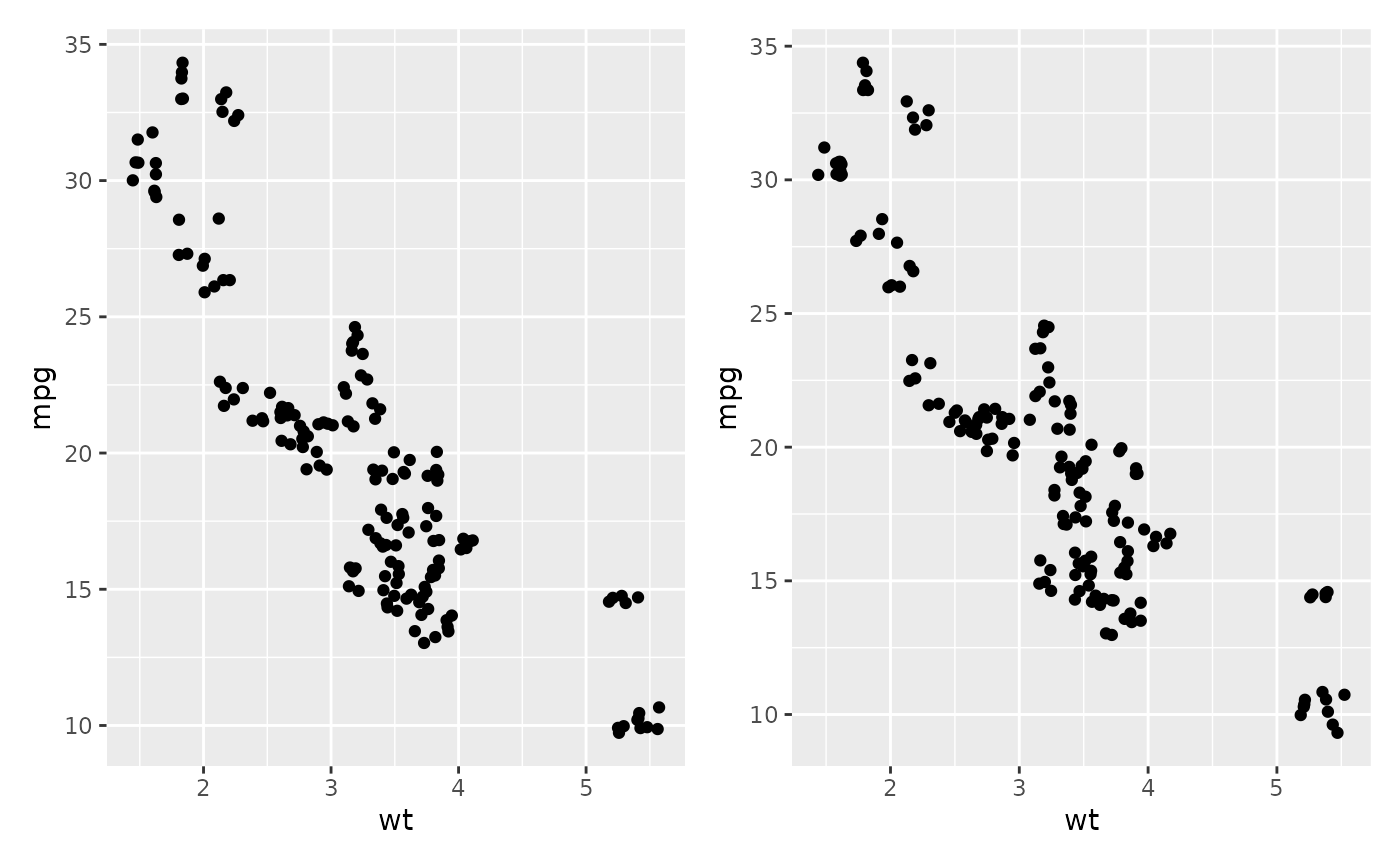

The two scatter plots above were called using the same variable

plot and would be identical if they were a ggplot, but you

can see they are slightly different.

Calling the same variable twice

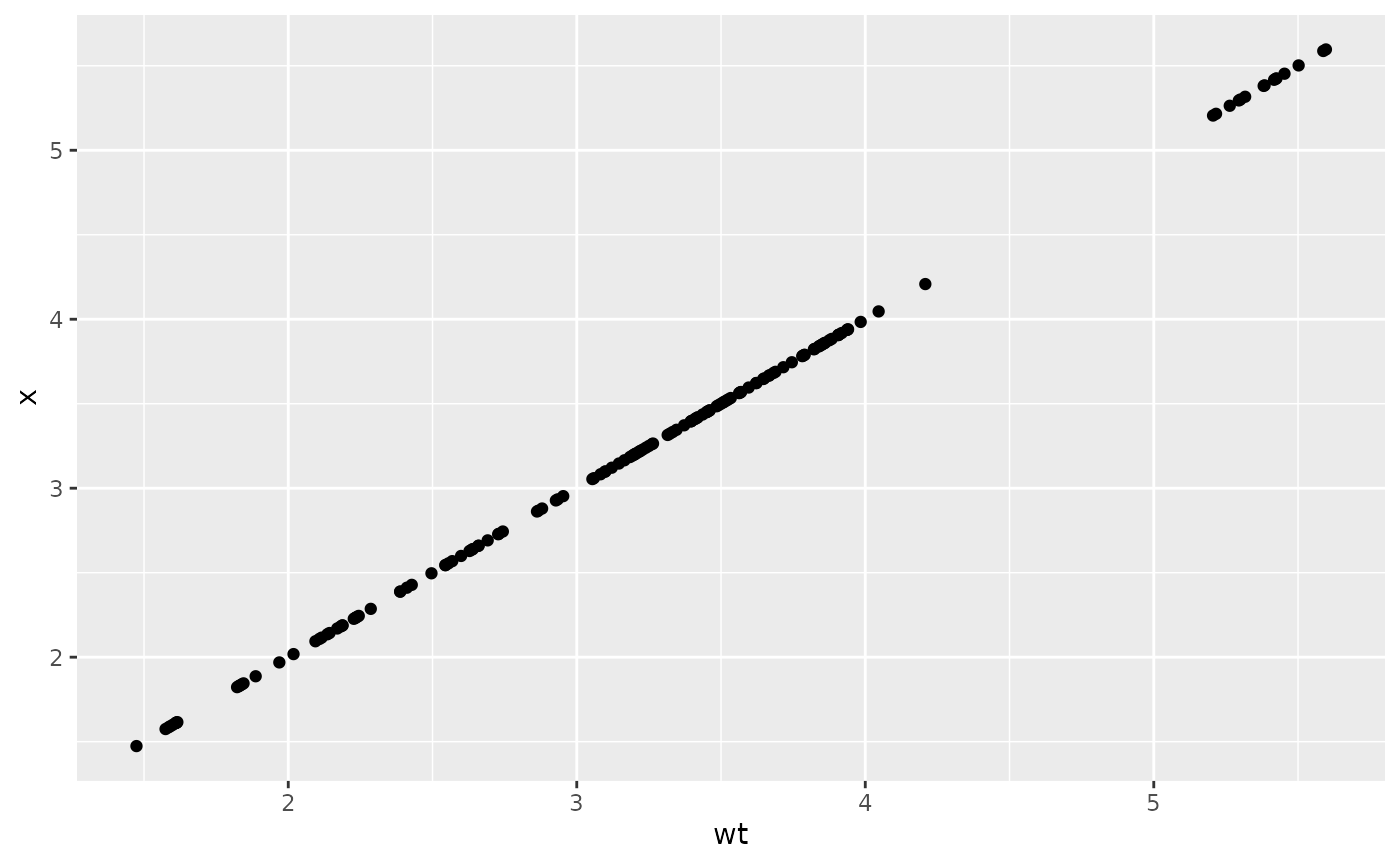

ggdibbler assumes all aesthetic distributions passed are

independent, which means if you pass the same variable to two different

aesthetic, they will be different samples.

p1 <- ggplot(mtcars, aes(wt, wt)) + geom_point() +

ggtitle("ggplot2")

p2 <- ggplot(uncertain_mtcars, aes(wt, wt)) + geom_point_sample(times=5) +

ggtitle("ggdibbler")

p1 + p2

By the time your data gets to the Stat stage of the plot computation,

we no longer have the variable names. This means we can’t be sure which

variables are actually identical versus which variables only appear to

be identical. You can get the identical behaviour by one of the draws

using the after_stat function.

ggplot(uncertain_mtcars, aes(wt, after_stat(x))) + geom_point_sample(times=5)

This issue is particularly problematic when you have multiple layers

using the same variable where the after_stat trick no

longer works. In this case so you will need to use the seed parameter to

ensure the draws are the same.

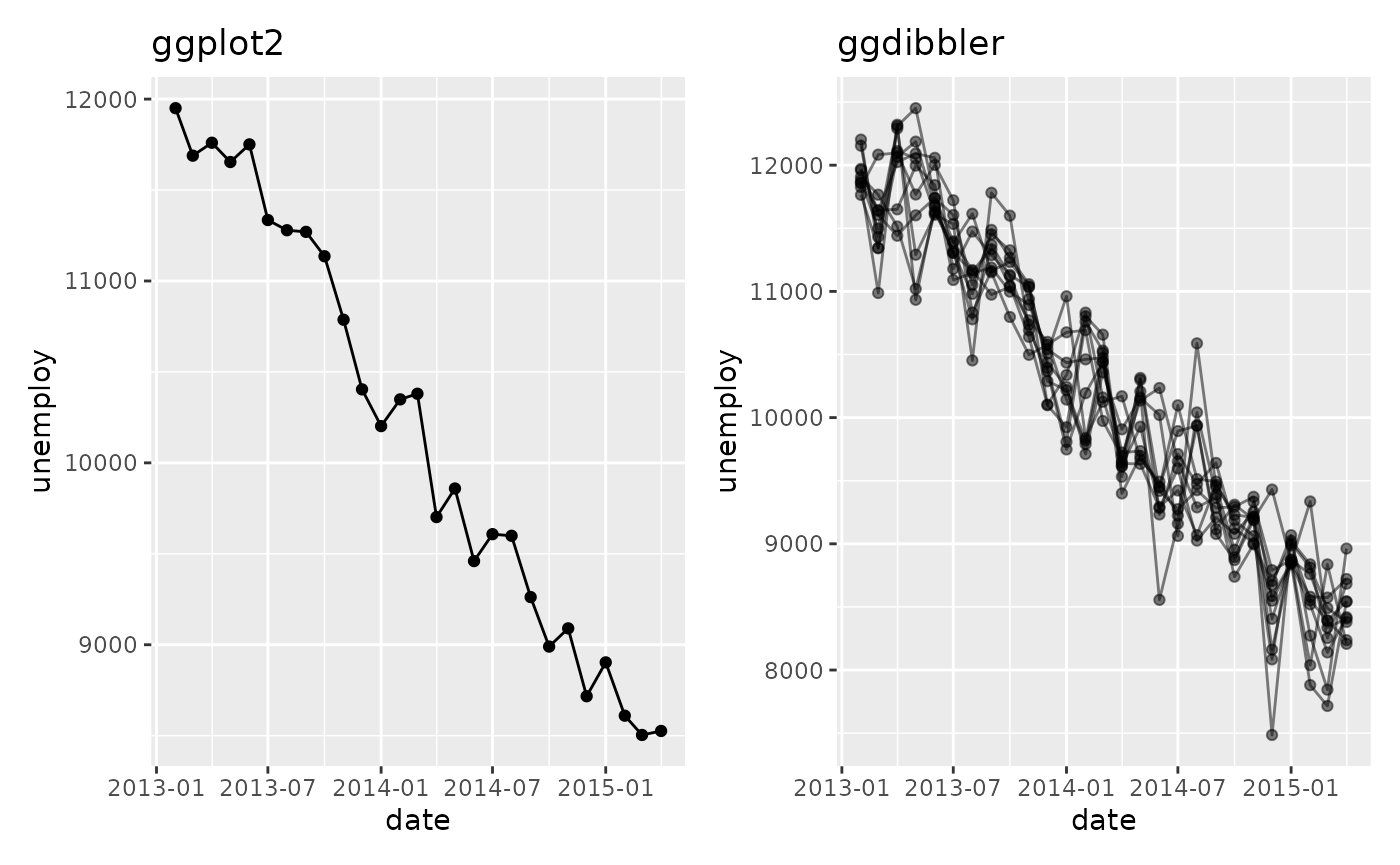

recent <- economics[economics$date > as.Date("2013-01-01"), ]

uncertain_recent <- uncertain_economics[uncertain_economics$date > as.Date("2013-01-01"), ]

p1 <- ggplot(recent, aes(date, unemploy)) +

geom_line() +

geom_point() +

ggtitle("ggplot2")

p2 <- ggplot(uncertain_recent, aes(date, unemploy)) +

geom_line_sample(alpha=0.5, seed=5)+

geom_point_sample(alpha=0.5, seed=5) +

ggtitle("ggdibbler")

p1 + p2

Random variables don’t always “look” random

In showing ggdibbler to people, I have noticed that

there are a few instances where the package does not behave in the way

they expect. Sometimes this is because of a bug on the packages part,

but I have also found that it can be because people are unsure what they

mean when they talk about uncertainty. ggdibbler will

always show you the plot you asked for, but it might not always be the

plot you think you asked for. This will be easiest to see with an

example.

Let’s say we are looking at the smaller_diamonds dataset

(which is just the diamonds dataset from

ggplot2, but… smaller) and we want to predict the cut using

the other variables. We make our fancy shmancy model, and then get a

predicted value for each class. Since our output is a prediction, we now

have a cut_true column, (our ground truth) and a

cut_pred which is our predicted distribution.

## # A tibble: 6 × 11

## cut_pred cut_true carat color clarity depth

## <dist> <ord> <dbl> <ord> <ord> <dbl>

## 1 Categorical[5] Very Good 0.55 F VS2 62.1

## 2 Categorical[5] Premium 2 G SI2 61.7

## 3 Categorical[5] Ideal 0.31 F VVS2 61.6

## 4 Categorical[5] Premium 1.52 I SI1 60.5

## 5 Categorical[5] Good 1.01 G VS2 62

## 6 Categorical[5] Ideal 0.82 I VS1 61.3

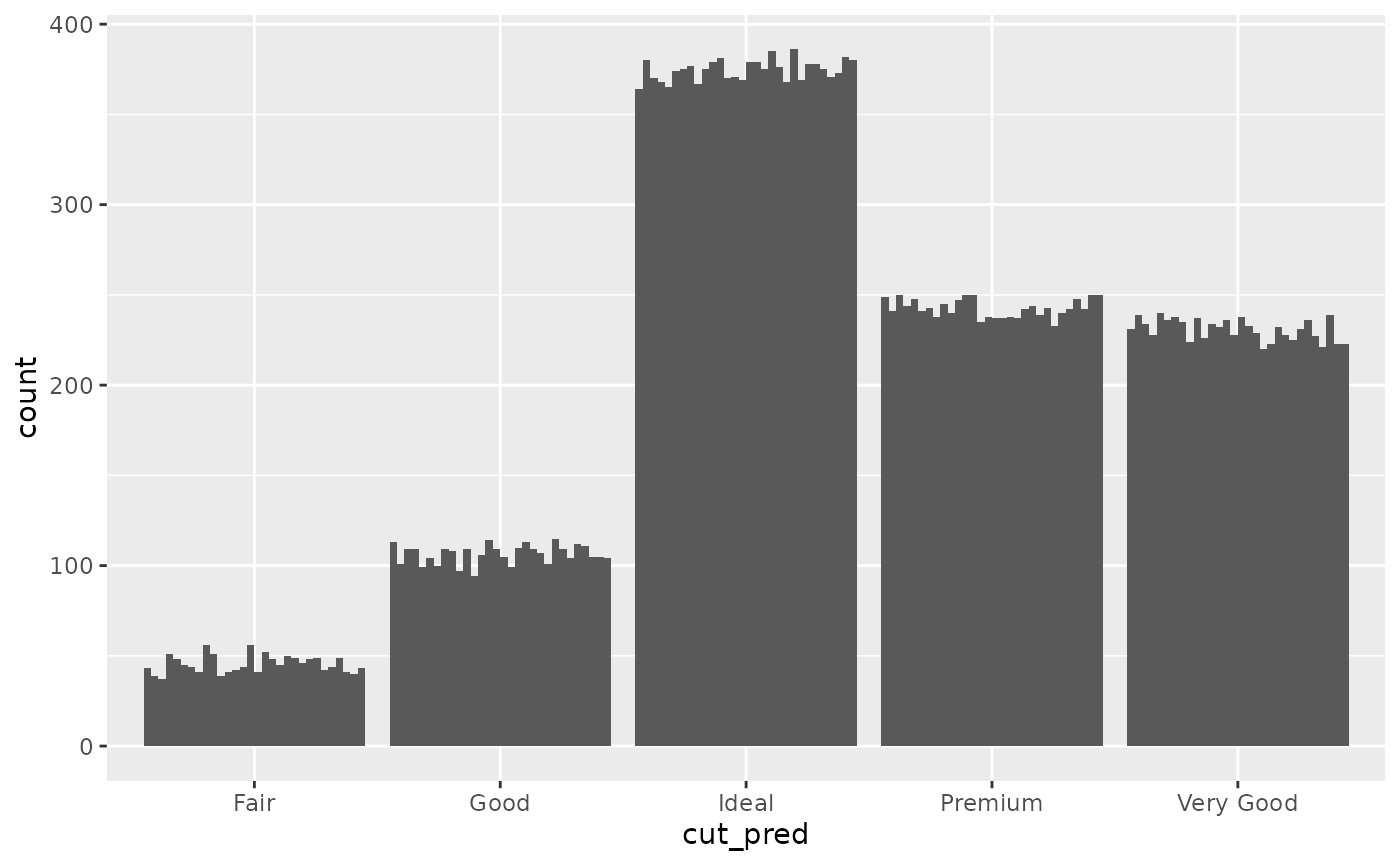

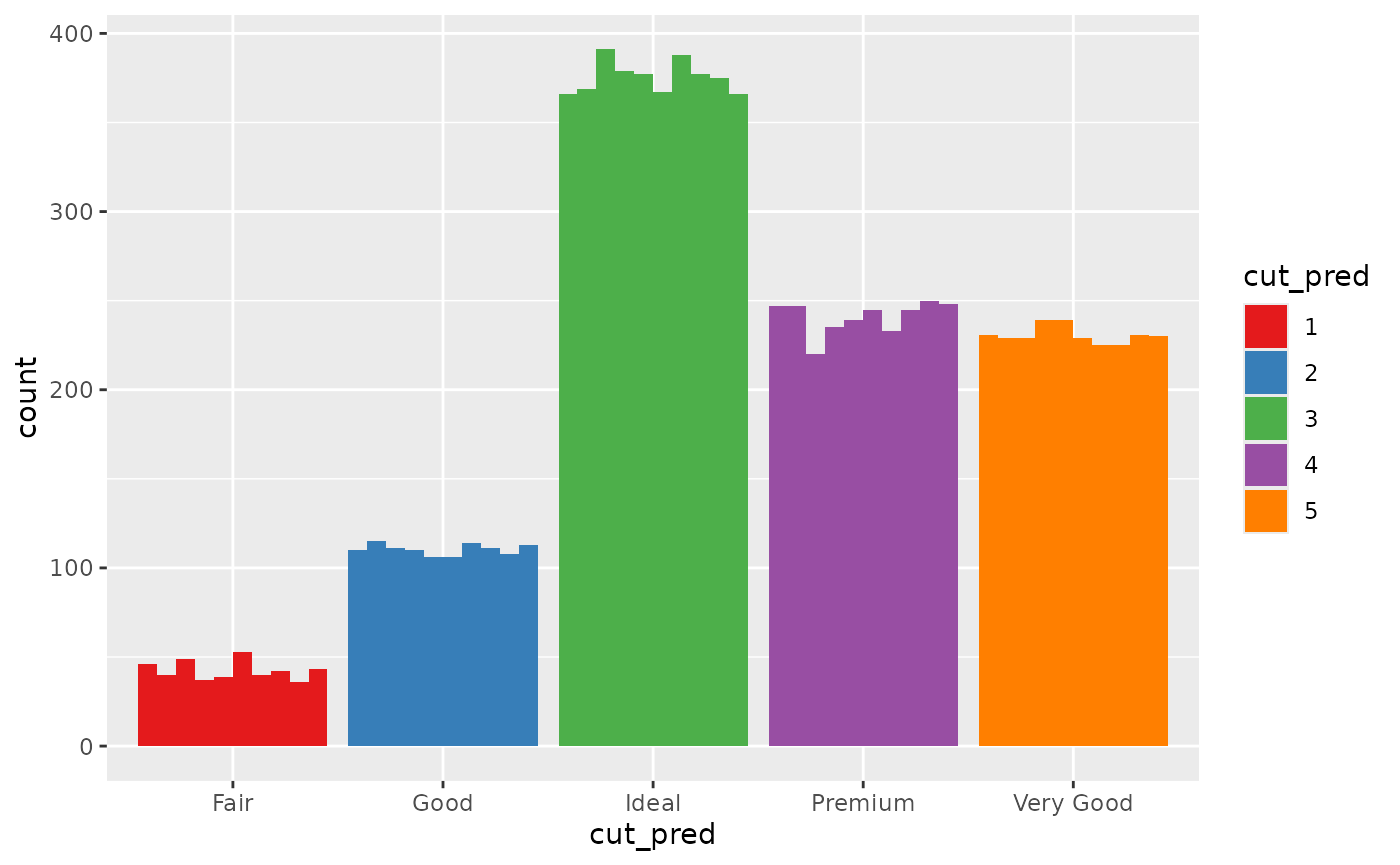

## # ℹ 5 more variables: table <dbl>, price <int>, x <dbl>, y <dbl>, z <dbl>You might want to know how many values end up in each group and how certain the model is in that prediction, so, you make the following bar chart:

ggplot(diamonds_pred, aes(x=cut_pred)) +

geom_bar_sample(times=30) Looking at this plot, it is clear that the count value is uncertain, but

that uncertainty is coming from the uncertainty in the cut_prediction.

The cut_pred values don’t look very “uncertain”, because in this plot,

they are not. This is the reality of visualising uncertainty for signal

suppression. Since the

Looking at this plot, it is clear that the count value is uncertain, but

that uncertainty is coming from the uncertainty in the cut_prediction.

The cut_pred values don’t look very “uncertain”, because in this plot,

they are not. This is the reality of visualising uncertainty for signal

suppression. Since the stat_sample that is used to get

outcomes from the distribution is nested inside of ggplot’s

stat_count, the uncertainty in the prediction is carried

through to the variable the plot is designed to show, i.e. the count in

each category. If it makes you feel better, we can set the fill to be

the outputs so you can 100% see this is the case.

ggplot(diamonds_pred, aes(x=cut_pred)) +

geom_bar_sample(aes(fill=factor(after_stat(x))), times=30) +

labs(fill = "cut_pred")+

scale_fill_brewer(palette = "Set1")

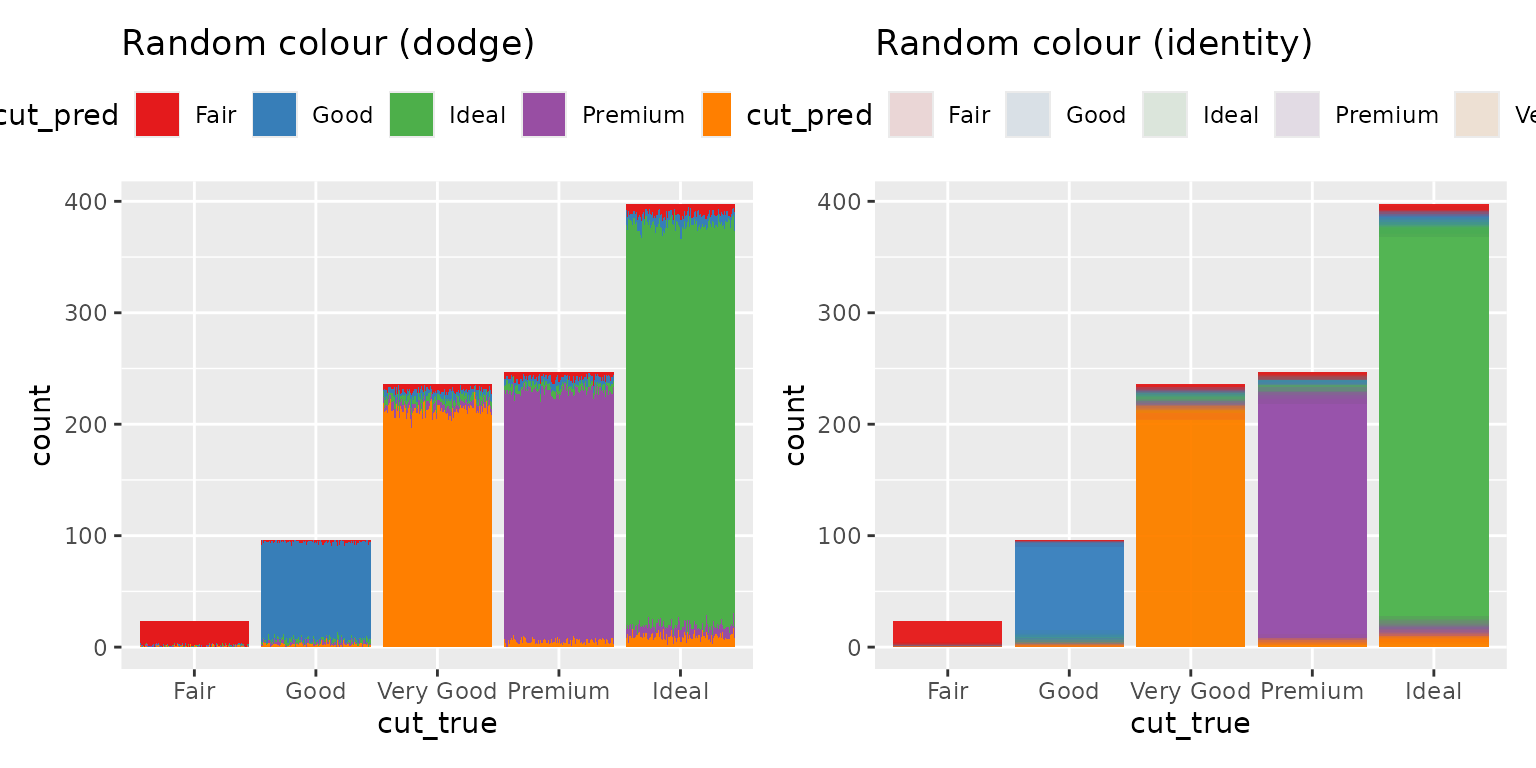

Of course, you can also set the fill to be a second independent draw from the prediction distribution, but this would convey the wrong information. You would be implying far more uncertainty than is actually in the bar chart. Instead of drawing from one distribution, we are drawing from two independent distributions that technically represent the same variable.

The reality is, distribution variables do not have a set value, so if

their position on the x axis and their colour are not set by the

after_stat distribution outcomes …. what are they set by?

If you want the random variables anchored to a deterministic variable,

YOU need to decide what to anchor them to. You need to decide what your

random variables are conditional on. If you want them conditional on the

deterministic true value, you need to do that. Here is an

example where they are anchored to the ground truth value and we colour

by the prediction.

p2 <- ggplot(diamonds_pred, aes(x=cut_true)) +

geom_bar_sample(aes(fill= cut_pred), times=100,

position= "stack_dodge") +

theme(legend.position="top") +

scale_fill_brewer(palette = "Set1") +

ggtitle("Random colour (dodge)") +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

p3 <- ggplot(diamonds_pred, aes(x=cut_true)) +

geom_bar_sample(aes(fill= cut_pred), times=100, alpha=0.1,

position= "stack_identity") +

theme(legend.position="top") +

scale_fill_brewer(palette = "Set1") +

ggtitle("Random colour (identity)") +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

p2 + p3

The height of the bar represents the total number of values predicted as that class, and the proportion of the the bar that is filled in as that colour represents the probability that the observation is that class. You will notice that the y-axis now represents the count of a deterministic variable (so there is no random variation and it is easy to read) but the colour is random, so it does have variation.